The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

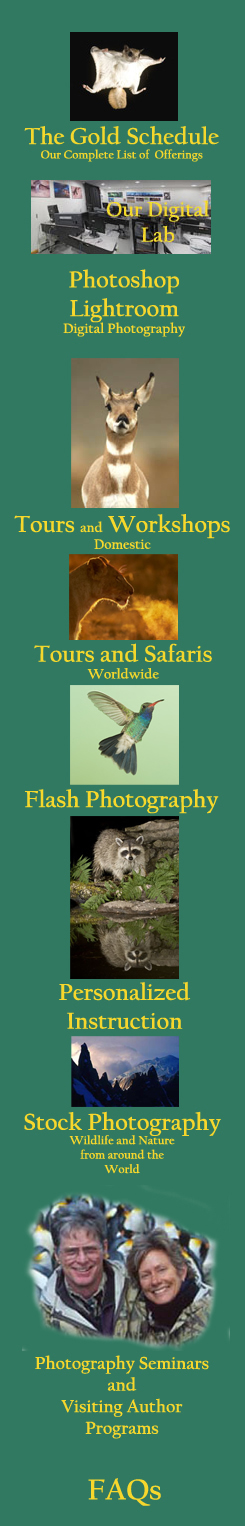

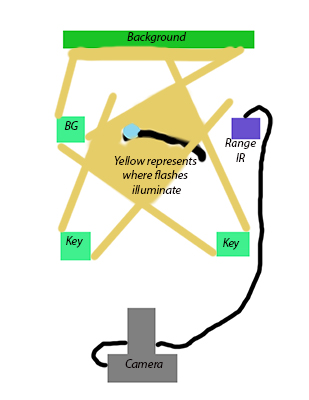

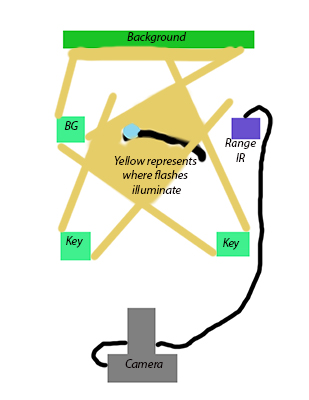

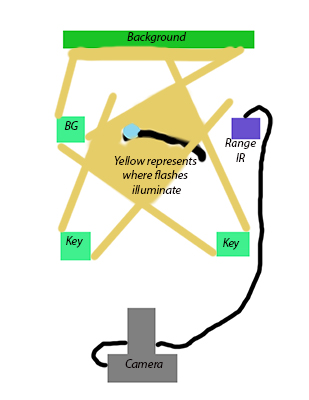

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

Past Stories Behind the Photograph

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Jumping American Toad

Bats in Costa Rica

African Bats

The Ocelot

The Waterhole

Bushbaby

Barn Swallow

King Penguin

The Lion and the Landscape

The Bighorn Sheep

The Raccoon

The Pileated Woodpecker

The Striking Rattlesnake

The Pink Salmon

The Spectacled Caimen

Office Phone: (717) 543-6423

Or email us at: info@hoothollow.com

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

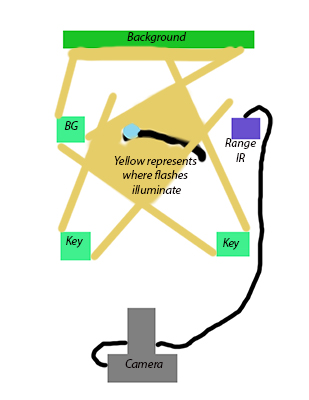

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

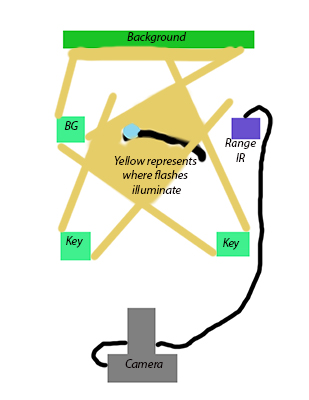

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

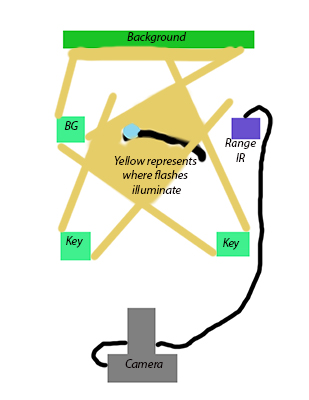

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

The Story Behind the Photograph

Photographing Flying Birds at a Feeder

A few weeks ago I finished our Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course, a course I had not offered for seven years. One of the projects students could work on was capturing a bird in flight. All summer, I had been conditioning Tufted Titmice, Eastern Phoebes, Blue Jays, Carolina Wrens, and other birds to a few sites, using mealworms for bait. On the covered porch by my office we had a safe, weather-proof area where equipment could be placed without fear of a sudden rain storm closing the shoot down, or ruining equipment.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

In this month's Question of the Month, I noted that the efforts of my students motivated me to make the same type of images my students were attempting. While they had difficulty, because of a lack of familiarity with the gear, had they had experience the exercise would have been fairly easy. The real difficulty is not in placing the flashes or the camera-tripping beam, it is having a bit of luck that a bird will fly through the beam at the right spot to be framed and in focus.

Had I used the Cognisys High-Speed Shutter, this difficulty would be reduced, as the shutter would fire almost  instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

instantaneously, so a bird breaking the Range IR beam would be capturedalmost right at that spot. Since my students were limited to just using the Range IR, I used the same gear. However, when I'm doing some very serious work, like catching a rattlesnake in mid-strike, I use the high speed shutter!

For these shots I went quite simpe, using a Range IR to trip the camera, three Phottix remote triggers to fire three flash units set on manual mode at 1/32nd power, four Manfrotto lightstands, and one Manfrotto Magic Arm and SuperClamp to support an out of focus canvas photograph that served as the background. I had a perch that I hollowed out to accommodate a small plastic cup where I placed a handfull of mealworms. This was important, as the smooth plastic kept the mealworms inside the container, otherwise they'd crawl out and the birds could feed anywhere, and not at my target area.

In the diagram to the left, I've outlined the setup. The green boxes, labeled BG and Key, represent the flashes. The BG flash illuminated the background. I had two Key flashes to cover the perch. The Range IR was placed a bit behind the perch (the blue circle represents the mealworm feeder) and the infrared beam was placed to intercept the birds as they flew in to the mealworms. Not shown is another perch, placed high and behind the feeder, where the birds often perched before flying in to the mealworms.

If the Range IR was aimed right at the feeder most, if not all, of the images would have had the birds perched on the branch, probably with the wings already closed. Although it takes a little trial and error, it doesn't take long to work out how far the bird travels before the camera fires, and to then position the Range IR far enough away so that the wings are still open when the camera fires. All digital cameras have a lag time, which is the time between when the Range IR is tripped and the camera actually fires. This can be as long as 1/10th of a second with some cameras, and is camera specific, not necessarily the model of the camera.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

When a Range IR is attached to a flash, the response is instantaneous, and there is no lag. However, in that case the shutter must be open prior to the flash firing, so the shutter must be advanced continually, at a very slow shutter speed, or set on bulb. That's the technique I used for the insects I shot after the course.

In the case of the insects, the procedure was similar, but the flashes were set to 1/64th power, to freeze the action. Focus, obviously, is critical.

Although there's a bit of down-time involved in setting these shots up, once done I can let my system do the work while I write a Tip of the Month, or an article for Nature Photographer, or get a well deserved night's sleep if I'm hoping to photograph nocturnal wildlife in the Pantanal.

The trick is knowing your gear, knowing what you need, and orchestrating the set so that your subject flies, walks, crawls, or hops, where you have your lens aimed and focused, and the flashes set to catch the action. I love the Range IR for this because of its small size, allowing me to easily pack several for different projects on trips, and the fact that it uses AA batteries for power.

If there is sufficient interest, I will offer an Advanced Digital Nature Photo Course devoted to flash and high speed flash and remote camera tripping devices, like what I'm illustrating on this page, in late July of 2014. Exact dates are not yet determined, but you can contact our office to be placed on our first contact list.

Past Stories Behind the Photograph

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Jumping American Toad

Bats in Costa Rica

African Bats

The Ocelot

The Waterhole

Bushbaby

Barn Swallow

King Penguin

The Lion and the Landscape

The Bighorn Sheep

The Raccoon

The Pileated Woodpecker

The Striking Rattlesnake

The Pink Salmon

The Spectacled Caimen

Past Stories Behind the Photograph

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Jumping American Toad

Bats in Costa Rica

African Bats

The Ocelot

The Waterhole

Bushbaby

Barn Swallow

King Penguin

The Lion and the Landscape

The Bighorn Sheep

The Raccoon

The Pileated Woodpecker

The Striking Rattlesnake

The Pink Salmon

The Spectacled Caimen

Office Phone: (717) 543-6423

Or email us at: info@hoothollow.com